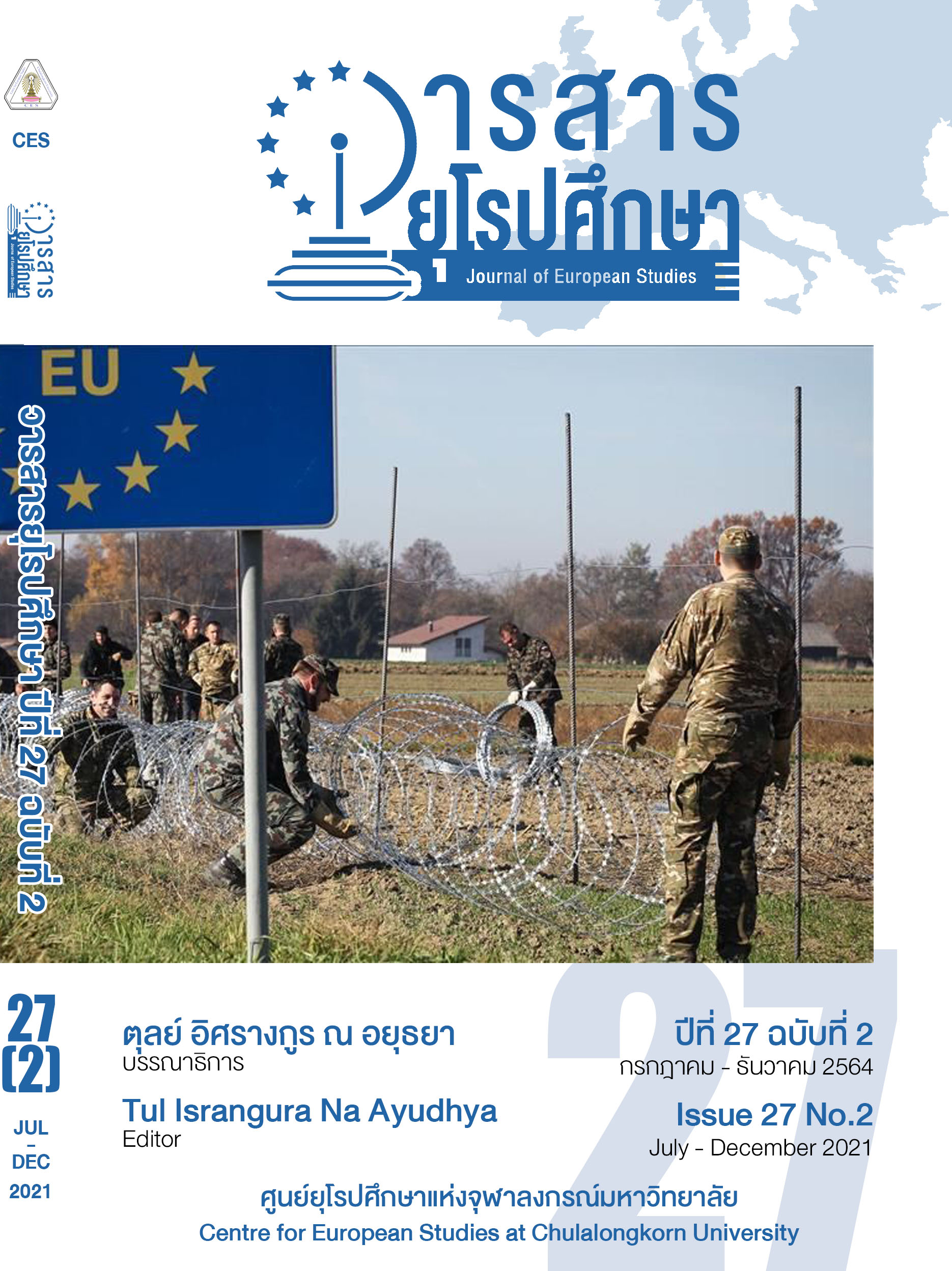

Normative Power vs. National Interests in the Policy-Making Process of the EU Relating to Refugee Crisis:

Case Study of EU-Turkey Deal

Keywords:

Normative Power, European Union, The EU-Turkey Deal, National Interest, NormsAbstract

‘Normative Power’ is one of the most important powers of European Union. With a hope for the existing and new norms to be accepted by its members and international actors. Its mission is to shape conceptual, and to build rules and ideas of ‘the common goods.’ Through the study of refugee crisis in Europe, norms are diffused thanks to procedural diffusion, which is where European Union’s organs and institutions play a great role. The EU-Turkey deal was made and hoped to tackle the refugee problems. It comes up with various measures, such as returning of irregular migrants, control of migration, and one-to-one policy. This is a significant start from two cores international actors to deal with transborder problems. Unfortunately, the deal is not the best one possible. Some crucial problems still occur; reluctant of Turkey towards the EU, an unsuccessful settlement of norms, an unbinding agreement, a damaged portray of NPE and the most important one, harms towards refugees and their rights. These failures combined with Intergovernmentalism theory help us to explore that norms are, however, not the main priority of any policy, but a national interest. European Union is used by its members to express their interests, which on another hand can be interpreted that norms has not been settled even within the Union itself.

References

Amy Verdun, “Intergovernmentalism: Old, Liberal, and New” University of Victoria, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1489.

Andrew Moravcsik and Frank Schimmelfennig, “Liberal Intergovernmentalism” in European Integration Theory, 3rd ed., (Oxford University Press, 2019).

Annett Meiritz and Dara Lind, “Why Germany just closed its borders to refugees,” Vox, 14 September 2015, https://www.vox.com/2015/9/13/9319741/germany-borders-merkel (accessed on 10 December 2020).

Bianca Benvenuti, The Migration Paradox and EU-Turkey Relations, (Istituto Affari Internazionali, 2017).

Canan E. Tabur, 2012, The decision-making process in EU policy towards the Eastern neighbourhood: the case of immigration policy, Philosophy in Contemporary European Studies University of Sussex.

“Erdogan vows to keep doors open for refugees heading to Europe,” Aljazeera, 29 February 2020, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/2/29/erdogan-vows-to-keep-doors-open-for-refugees-heading-to-europe (accessed on 7 December 2020).

Ian Manners, The Concept of Normative Power in World Politics, (Danish Institute for International Studies, 2009).

Ian Manners, “Normative Power Europe: A Contradiction in Terms?,” JCMS Vol. 40, No. 2 (2002): 238-239.

Kim Rygiel, Feyzi Baban, Susan Ilcan, “The Syrian refugee crisis: The EU-Turkey ‘deal’ and temporary protection,” Global Social Policy 2016, Vol. 16, No.3: DOI:10.1177/1468018116666153.

Manfred Weber, “EU-Turkey relations need an honest new start,” European View 2018, Vol. 17, No. 1: DOI: 10.1177/1781685818765095.

Mark Provera, “The EU-Turkey Deal: Analysis and Considerations,” Jesuit Refugee Service Europe, 2016, https://jrseurope.org/assets/Publications/File/JRS_Europe_EU_Turkey_Deal_policy_analysis_2016-04-30.pdf.

Muhammad Hussein, “Remembering Alan Kurdi,” MiddleEastMonitor, 2 September 2020. https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20200902-remembering-aylan-kurdi/ (accessed on 13 December 2020).

Thomas Diez, “Normative power as hegemony,” Cooperation and Conflict Vol. 48, No.2 (2013): DOI: 10.1177/0010836713485387.

Thomas Diez and Michelle Pace, “Normative Power Europe and Conflict Transformation,” ResearchGate 17 September 2014, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/29997518_Normative_Power_Europe_and_Conflict_Transformation (accessed on 11 November 2020).

ณัฐนันท์ คุณมาศ, “ทฤษฎีในการศึกษาสหภาพยุโรป: จากการบูรณาการ นโยบายทางเลือก สู่กระบวนการยุโรปภิวัตน์,” วารสารยุโรปศึกษา ปีที่ 42, ฉบับที่ 1 (2555): 138-141.